Dolly Wilde’s Picture-Show

Artist statement by Rebecca Nesvet

“And still they come and go: and this is all I know–

That from the gloom I watch an endless picture-show…”

Siegfried Sassoon, “Picture-Show” (1920)

Playwrite Rebecca Nesvet about her Dolly Wilde’s Picture-Show

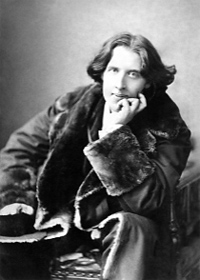

When I read Sassoon’s ‘Picture-Show’, the poem doesn’t call up only the ghosts of the fallen ‘men’ eulogized in the second verse. It also recalls other veterans of the First World Wars, who afterwards felt as haunted as did Sassoon: the women who served as nurses, telegraph-operators, and ‘motor-drivers’, including drivers of Red Cross and privately-operated ambulances. Among those women was Dorothea Ierne (‘Dolly’) Wilde (1895-1941), niece of Oscar Wilde (1854-1900) [see vintage photo]. Dolly’s story intrigued me. What brought her to the front? What had she experienced there? How might it have shaped her later life, and perhaps her youthful death?

When I read Sassoon’s ‘Picture-Show’, the poem doesn’t call up only the ghosts of the fallen ‘men’ eulogized in the second verse. It also recalls other veterans of the First World Wars, who afterwards felt as haunted as did Sassoon: the women who served as nurses, telegraph-operators, and ‘motor-drivers’, including drivers of Red Cross and privately-operated ambulances. Among those women was Dorothea Ierne (‘Dolly’) Wilde (1895-1941), niece of Oscar Wilde (1854-1900) [see vintage photo]. Dolly’s story intrigued me. What brought her to the front? What had she experienced there? How might it have shaped her later life, and perhaps her youthful death?

While investigating these questions, I encountered SPIR Conceptual Photography (Jill Casid and María DeGuzmán)’s 1994 photo series Oscaria/Oscar (see photo below), which in a kind of modern, color spirit-photography imagines interactions between Dolly and her uncle, Oscar Wilde [see vintage photo] — or perhaps Dolly and herself, posing as her uncle — or even Oscar and his double on (pace Dorian Gray) the other side of a frame.

It’s a haunting tribute to a Lost Generation — Dolly’s, perhaps, but certainly the Lost Generation of the 1980s-90s: the earliest victims of the HIV-AIDS epidemic; the generation to which Dolly’s uncle might have belonged, had he been born a century later than he was. How, Casid and deGuzmán have asked, can we ‘love our dead back to life?’ In Oscaria/Oscar, they show Dolly trying to do this, and maybe Oscar loving (albeit perhaps in a self-regarding way) his niece to a fully-realized life as an early-twentieth-century lesbian. Like Sassoon’s cinema of post-combat nightmare, Oscaria/Oscar is a dynamically paranormal ‘Picture-Show’.

It’s a haunting tribute to a Lost Generation — Dolly’s, perhaps, but certainly the Lost Generation of the 1980s-90s: the earliest victims of the HIV-AIDS epidemic; the generation to which Dolly’s uncle might have belonged, had he been born a century later than he was. How, Casid and deGuzmán have asked, can we ‘love our dead back to life?’ In Oscaria/Oscar, they show Dolly trying to do this, and maybe Oscar loving (albeit perhaps in a self-regarding way) his niece to a fully-realized life as an early-twentieth-century lesbian. Like Sassoon’s cinema of post-combat nightmare, Oscaria/Oscar is a dynamically paranormal ‘Picture-Show’.

I decided that its pictures ought to move and change, like Dorian’s picture, and to interact with the three-dimensional, living Dolly. Which means that Oscar/Oscaria had to be adapted as theatre.

My first attempt at that adaptation, Dolly Wilde’s Picture-Show, will be presented as a workshop production, with projections from Oscaria/Oscar, as part of the Process Series at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, in August 2014. [Further details about the performance below.]

My first attempt at that adaptation, Dolly Wilde’s Picture-Show, will be presented as a workshop production, with projections from Oscaria/Oscar, as part of the Process Series at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, in August 2014. [Further details about the performance below.]

Why must Dolly’s life be told as a living ‘Picture-Show’? Because Sassoon’s poem presents an unusually accurate approximation of her memory; of her imaginative life; and of the way that those acquaintances, friends, and lovers who survived her remembered her, because for many of them, Dolly wasn’t just a First World War private ambulance driver. She was also a prominent member of a lesbian (mainly), feminist (unanimously) literary-artistic circle based at the home of her American lover Natalie Clifford Barney, at 21 Rue Jacob, Paris. So when she died, frustratingly young, she was mourned by very expressive women.

Also, she was both apparitional and clairvoyant. She was often seen as her uncle’s double, ‘ghosting’ him: Barney called her ‘Oscaria’ (posthumously, at least) and H. G. Wells, perhaps seeing her as a time-traveller rather than an apparition, called her a ‘feminine [Oscar] Wilde’. That was a persona she not only owned, fiercely, but radically reinvented. No doubt to Barney’s delight, Dolly attended a 1930 costume ball posing ‘as Oscar’. But she was no mirror image. A surviving, undated photograph shows Dolly dressed appropriately, in the ‘aesthetic’ collar shirt, puffy, loose bow-tied silk cravat, and fur-lapelled coat in which Oscar posed for the New York society photographer in 1882, and which became his indelible public image to this day. It’s an image associated with independence and freedom and cultural authority, for it was his costume when he crossed North America by rail, lecturing on the Aesthetic movement, European artists, and interior decorating as part of an engagement by Robert d’Oyly-Carte’s opera company, which was satirizing Aestheticism in Gilbert and Sullivan’s Patience. So, at the costume ball, Dolly poses as an authority on art and artists (such as the Renaissance Women of the Rue Jacob?) and an intrepid traveler, which she also was, though her mode of travel was the motor-car. But she also differentiates herself from her uncle. She wears makeup, highlighting not necessarily her femininity, but the theatricality of femininity itself. She self-consciously fashions herself both ‘feminine’ and ‘Wilde’.

Moreover, Dolly’s very act of ‘posing’ as her uncle but not emulating him to the point of self-disappearance (as did her Wilde-forger cousin Arthur Cravan) is a paradoxical kind of ghosting, and a gift to her ancestor. Oscar Wilde’s troubles with British law began in 1985 when John Sholto Douglas, Marquess of Queensberry, put into circulation a calling card addressed to Wilde ‘posing as a somdomite [sic]’. Queensberry did this to interfere with his son, Lord Alfred Douglas’s, three-year-long relationship with Wilde, of which parts of the public were aware. Apparently not wishing to ‘out’ his son in an era when sodomy was dangerously criminalized, Queensberry claimed that Wilde was only ‘posing’ as a man who has same-sex relations. By combining theatrical womanhood with a Wildean persona, Dolly gives her uncle’s ghost a chance to affirm his truth, by affirming hers, for she was not just ‘posing’ as a lesbian: she was owning this truth. In most ghost stories, when the living help the ghost to live up to their abandoned responsibilities, the ghost is allowed to rest in peace. Perhaps that was the gift she gave her uncle, in exchange for the gift of family precedent that he gave her, to equip her for her messy but revolutionary life.

DOLLY WILDE’S PICTURE-SHOW

Script by Rebecca Nesvet

Featuring Marie Garelick and Paula Nance

Directed by Joseph Megel

Design by Kevin Spellman

Incorporating images from Oscaria/Oscar (1994), © SPIR Conceptual Photography (María DeGuzmán and Jill Casid)

Thursday, August 21 at 8:00 pm

Friday, August 22 at 8:00 pm

Swain Hall, Studio 6

University of North Carolina (UNC-Chapel Hill), USA

FREE and open to the public

[Photo Above : Dolly Wilde, vintage photo. Oscar Wilde, vintage photo. “Oscaria / Oscar” Photo: #3 in a sequence of 6 with the collaboration of Camille Norton and Jane Picard. Copyright © 1994 by Jill Casid & María DeGuzmán]

About Rebecca Nesvet

Rebecca Nesvet (PhD, English, UNC-Chapel Hill, 2014; MFA, Dramatic Writing, New York University, 2008) is a professor of English at the University of Wisconsin, Green Bay. She has won the 2002 Arch and Bruce Brown Playwriting Award for LGBT history plays, a 2007 Alfred P. Sloan Foundation Writing Grant, and the International Conference on Romanticism’s 2012 Lore Metzger Prize. Her research is published in WOMEN’S WRITING, THE KEATS-SHELLEY JOURNAL, and PRISM(S): ESSAYS IN ROMANTICISM, and she is editing Mary Russell Mitford’s banned play CHARLES THE FIRST (1824) for the Digital Mitford.